In response to an article, Ken Hughes: The Myth That Congress Cut Off Funding for South Vietnam

================

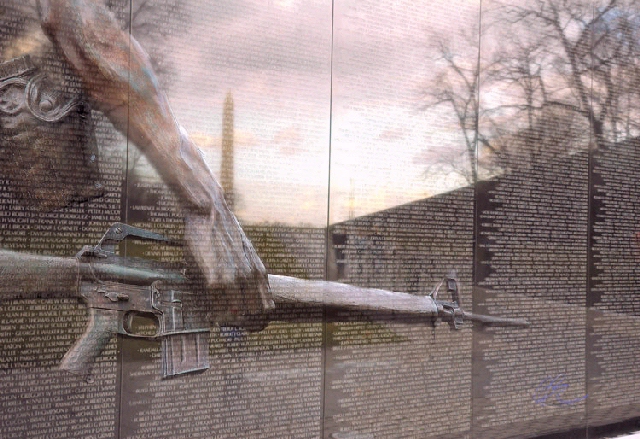

I don’t doubt Mr. Hughes sincerity, and as a technical matter he is correct that Congress did not totally cut off assistance to South Vietnam in 1975; but as a scholar who has been studying and writing about Vietnam for more than forty-five years (who was the last congressional staff member to leave Vietnam during the April 1975 final evacuation), I can assure you that the U.S. Congress was the most decisive factor in the Communist conquest of South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia in 1975.

To keep things in context, it is important to note that in the post-war era, Hanoi has repeatedly admitted that its leaders made a decision on May 19, 1959, to open the Ho Chi Minh trail and send tens of thousands of soldiers and countless tons of equipment and supplies south to “liberate” South Vietnam by armed force. That was more than 5 years before the U.S. decided to send combat units to Vietnam, and our purpose was precisely the purpose for which we sent troops into South Korea in 1950 — to uphold the non-aggression principles of the UN Charter and oppose the expansion of Communism by force.

Viet Cong defectors used to laugh and express shock at how successful their campaign to portray the “National Liberation Front” to the west as something other than a classic Leninist “front” organization had been. (Hanoi actually published an English-language translation of the proceedings of the Third Party Congress in 1960, including the resolution it approved calling for “our people” in south Vietnam to set up a front under Party leadership three months before the NLF was allegedly formed by non-Communist resistance leaders in Ben Tre.) American “scholars” who fell for this ruse should be ashamed of themselves.

We also need to keep in mind that the tremendous increase in POL costs resulting from the Arab oil embargo (OPEC raised oil prices 70% in late 1973) meant that to sustain South Vietnam at 1973 levels aid for subsequent years would have to be substantially greater. In reality, in 1975 Saigon got about 20% of the aid we provided in 1973.

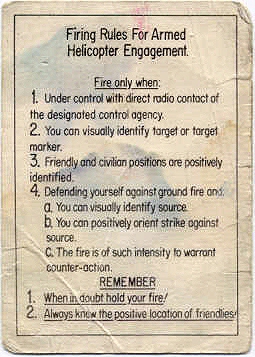

I traveled extensively through South Vietnam in 1968, 1970, 1971, and 1974, and I witnessed the effects of the aid cuts in ’74 and when I returned in ’75. Westmoreland claims that South Vietnamese soldiers were authorized one hand grenade per man per month, 85 rounds of ammo per month (about 7 seconds on full-auto in an M-16 — although in reality one would have to change magazines 3-5 times to fire that much ammo). Put another way, that provided about 3 rounds of ammo per day — ironically, the same amount defectors told me they had for the AK-47s following the highly successful 1970 Cambodian incursion, when they were instructed to put away their AK’s and dig up their old M-1 rifles and carbines, FALs, and the other relatively primitive weapons.) Each ARVN 105 mm howitzer was allocated 4 rounds of ammo per day, with only 2 rounds per 155 mm. Many of their tanks, helicopters, and fixed-wing aircraft were totally useless because of a lack of spare parts and/or fuel. And while Congress was cutting aid to Saigon, Moscow and Beijing were pouring aid into North Vietnam to fuel the war.

The United States made a solemn commitment by treaty in 1955 (when the SEATO Treaty drafted the previous year was ratified by Ike with almost unanimous advice and consent of the Senate–1 senator voted ‘nay’) to come to the aid of any of the “Protocol States” of that treaty requesting assistance in defense of their freedom from Communist aggression. Those “Protocol States” were the States of Vietnam [later the Republic of Vietnam or South Vietnam], Laos, and Cambodia. In August 1964, Congress enacted the Southeast Asian Resolution by a combined vote of 504-2 (a 99.6% majority). John F. Kennedy pledged to the world: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” Ironically, the leaders of the “save South Vietnam” drive in the mid-’50s were liberal, internationalist Democrats like Kennedy, Mansfield, and Fulbright.

The congressional action that truly sounded the death knell for South Vietnam and “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory” was not simply cutting aid, but passing a law (the FY 1973 Dep’t of State Auth. Act, Pub. L. 93-126, 87 Stat. 451) that provided:

“Notwithstanding any other provision of law, on or after August 15, 1973, no funds heretofore or hereafter appropriated may be obligated or expended to finance the involvement of United States military forces in hostilities in or over or from off the shores of North Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia, unless specifically authorized hereafter by Congress.”

As a constitutional scholar who wrote my doctoral dissertation of the separation of national security powers, I believe this provision was flagrantly unconstitutional. But it guaranteed Hanoi and its allies that the United States was not going to fulfill its solemn pledge to defend these victims of aggression, and Pham Van Dong (Hanoi’s Premier) announced that the Americans would not come back “even if we offered them candy.” So Moscow and Beijing greatly increased their aid, Hanoi left only the 325th Division to defend the Hanoi area and sent the rest of its Army behind columns of Soviet-made tanks to conquer South Vietnam (and Laos and Cambodia, the other Protocol States we had repeatedly pledged to protect) in a conventional military invasion.

I worked in the Senate (as national security adviser to Sen. Robert P. Griffin, a member of the Foreign Relations Committee) during the final period and sat through the public and closed hearings. I listened as Sen. Mike Mansfield assured some of his colleagues that he had just spoken with Sihanouk (who was in Beijing) by phone and had been assured that when the Khmer Rouge (“Red Cambodians”) seized power in Phnom Penh only a small number of leaders would be killed.

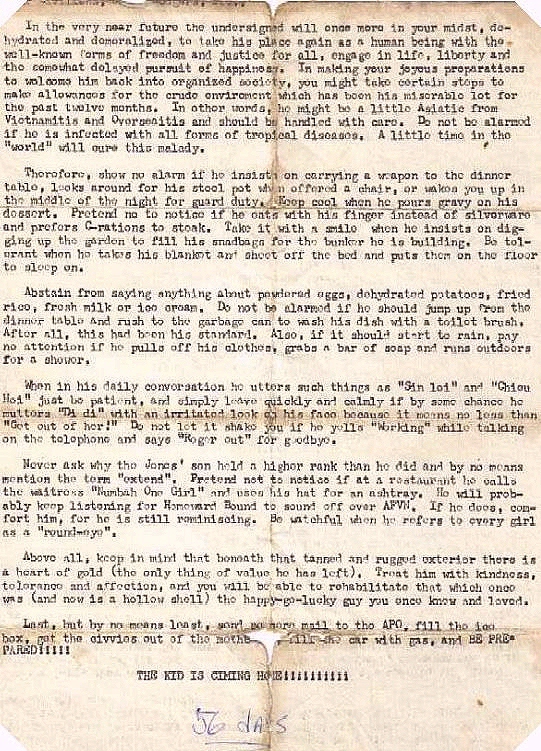

The reason I was back in Vietnam in 1975 was to assist with the orphan lift. The governor of Michigan had declared an “open door” policy, saying Michigan would find homes for any orphans we could rescue. While others in the group worked with South Vietnamese orphanages (ultimately abandoning them and fleeing to Hong Kong in fear), I worked on trying to arrange to rescue orphans in Cambodia on the empty C130 aircraft that each day flew rice into Cambodia. (http://www.virginia.edu/cnsl/images/Turner-CambodiaCable.jpg.) I was too late.

The consequences of the congressional decision to betray John Kennedy’s noble promise and the treaty and statutory pledges we had made to protect South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia are clear. An estimated 100,000 South Vietnamese were executed, as many as 250,000 more died in “reeducation camps,” and another 45-50,000 died in the “New Economic Zones. Using figures provided by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, an estimated 420,000 “boat people” died at sea fleeing the Communist tyranny in search of freedom. The best figures I’ve seen on Cambodia come from the Yale University Cambodian Genocide Project: 1.7 million Cambodians (more than 20% of the entire population) were killed by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge. A January 2004 article on the “killing fields” in NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TODAY noted that “bullets were too precious to use for executions. Axes, knives and bamboo sticks were far more common. As for children, their murderers simply battered them against trees.”

What Congress did in 1973-75 was shameful — among the darkest and most immoral years in the history of U.S. foreign policy. It led directly to Soviet intervention in Angola (and yes, Mr. Hughes will be correct if he notes that began about 1962 — but after we betrayed the non-Communist peoples of Indochina the Soviets started sending in what eventually became more than 400,000 Cuban “volunteers,” promoting a “civil war” that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. The Soviets authorized “armed struggle” in Central America that cost countless more lives, and an estimated million people died when Moscow invaded Afghanistan.

In the end, as the PENTAGON PAPERS confirmed to anyone who bothered to actually read them (http://www.virginia.edu/cnsl/pdf/Turner-Myths.pdf), the “peace movement” and congressional critics of the war were mistaken almost across the board in their arguments. And the human consequences of their betrayal of America’s honor were catastrophic.

Again, I’m not unhappy with Mr. Hughes. But from my perspective as someone who has followed this issue for nearly half-a-century, efforts to claim that Congress was not responsible for allowing the Communists to conquer South Vietnam and its neighbors are as off the mark as efforts to deny the Holocaust.

The American people were horribly misled by the media about what was actually transpiring in Indochina. The 1968 Tet Offensive was a tremendous military defeat for the Communists, and after the May Offensive of that same year the southern “Viet Cong” had ceased to exist as a serious fighting force. Regular North Vietnamese PAVN soldiers took over the fighting, and with only U.S. air support the South Vietnamese successfully blocked their 1972 Spring Offensive. As Prof. John Lewis Gaddis noted in Foreign Affairs in early 2005: “Historians now acknowledge that American counter-insurgency operations in Vietnam were succeeding during the final years of that conflict . . . .” Many of us who were there at the time saw that first hand. We broke Hanoi’s will in the Linebacker II operation, and there was a good chance that had we retained the option of returning with our B-52s on Guam we could have enforced the Paris Peace Accords. Hanoi had run out of SAM-2 missiles, and neither Moscow nor Beijing were willing to resupply them militarily — UNTIL they saw Congress throw in the towel.

If Mr. Hughes or anyone else would like to publicly debate this issue, I can be reached at (434) 924-4083

Respectfully,

(Prof.) Robert F. Turner, SJD

Center for National Security Law

University of Virginia School of Law

bobturner@virginia.edu

The following two videos are courtesy of LTC Thomas von Eschenbach, Lighthorse 6, from their deployment in Afghanistan which I’ve uploaded to YouTube for all to enjoy!

The following two videos are courtesy of LTC Thomas von Eschenbach, Lighthorse 6, from their deployment in Afghanistan which I’ve uploaded to YouTube for all to enjoy!